|

Editorial Review Product Description

Kenneth Trachtenberg, the witty and eccentric narrator of More Die of Heartbreak, has left his native Paris for the Midwest. He has come to be near his beloved uncle, the world-renowned botanist Benn Crader, self-described "plant visionary." While his studies take him around the world, Benn, a restless spirit, has not been able to satisfy his longings after his first marriage and lives from affair to affair and from "bliss to breakdown." Imagining that a settled existence will end his anguish, Benn ties the knot again, opening the door to a flood of new torments. As Kenneth grapples with his own problems involving his unusual lady-friend Treckie, the two men try to figure out why gifted and intelligent people invariably find themselves "knee-deep in the garbage of a personal life." ... Read more Customer Reviews (4)  Saul Bellow meets Woody Allen

Saul Bellow meets Woody Allen

A comedy on modern life and love with a plot that allows Bellow to explore his favourite themes on the role of higher culture in a world that worships the base;are we what we see or how we see the world?

It helps to know the plot a little beforehand,I re read after my first reading to fully re enjoy.

Ken is a Woody Allen type;the one when you're never sure if he'sneurotic or the world around him is.He idolises his Uncle Benn,a genius in the world of fauna but a hopeless innocent outside it. Ken sees it as his role to protect his Uncle. Benn was cheated out of millions in a real estate deal by his Uncle Vilitzer, a powerful political figure,something that doesn't interest Benn until he marries in haste (without consulting Ken) into the grasping Layamon family who urge Benn to get his share as Vilitzer is on the way down in the political game.

Bear the above in mind and you'll enjoy this first rate tragi-comedy.

'More die...' is perhaps more for veteran Bellow readers-at times you feel the editor should have pointed out to Bellow that the rest of us are 10 leagues below his intellect and he might be getting a bit esoteric, but one of the things I've always loved about books by Saul Bellow is the way he makes you thirst to know what he knows;read what he's read.First timers may not get the full kick out of this great book or want to re read after taking in the complex and wonderful plot.

A great work, witty and compassionate

A great work, witty and compassionate

`He wanted a statement about the radiation level increasing. Also dioxin and other harmful waste. It's terribly serious, of course, but I think more people die of heartbreak than of radiation.' Such is the premise of Saul Bellow's masterpiece, written at the probable height of his creative power and on a par with Herzog and The Dean's December.

In a refined and richly substantiated extemporisation, Bellow takes a sounding of the place of romance in contemporary life and makes the case that it remains of central if problematic concern. More Die of Heartbreak remains hugely current, and relevant. Modern fears and distractions continue to lay siege to the arguably paramount realms of sentimental and private fulfilment. Our world is even more so one of technicians and specialists, isolated in mutually inaccessible spheres. For this is what Bellow portrays: the difficulty of love when surrounded with the complexities of professional specialisation, money, sex, cultural doubt, moral and social flux. Also just the difficulty of love.

Benn Crader, a botanist, and his nephew Kenneth, another academic, struggle to reconcile intellectual achievement with unsatisfactory love and marital lives. The uncle marries the glamorous social climber Matilda Layamon in a second wedding, to find himself forced into a financial suit that will destroy his ties to his own family. Kenneth strives to fill the gap left by a painful break-up. Nothing much more happens in this ironic, rambling portrayal of floundering individuals who philosophise as they go. And to be fair, this is not for fans of action or quick-paced plots. But if you like reading Kundera or Philip Roth (who is a later writer and seems to me to owe much to Bellow), you will enjoy this novel. Bellow is impressively erudite but never pedantic and always entertaining and matter-of-fact. He tends to divagate, here from the dangers of bad skin to the morals of Hitchcock movies and to court politics, but he is extremely well informed and invariably interesting. There is also a point to his constant asides, namely to put the question of the adequacy of culture to real life.

And it is all told with an effective, deadpan humour. (`Benn was a botanist of a "high level of distinction"... They're relatively inexpensive too. It costs more to keep two convicts in Statesville than one botanist in his chair. But convicts offer more in the way of excitement - riot and arson in the prisons, garrotting a guard, driving a stake through the warden's head.' Or `Mother joined a group of medical volunteers stationed near Djibouti, where the famine victims died by the thousands, daily. She wore chino skirts, cheap cotton twill, as close to sackcloth as she could get.') Perhaps a little sarcastic, but who wants polite, deferential blandness?

Another Bellow Surprise: Turning the Tables Men vs Women

Another Bellow Surprise: Turning the Tables Men vs Women

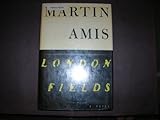

Just when you think that you understand Bellow, this book comes along. This is a new version with an interesting 17 page introduction by Martin Amis. It is based on a talk that he gave at a Bellow conference in Haifa, Israel.

I am a Bellow fan, read all of his novels, and wrote an Amazon guide: "A Guide to Reading Bellow." The present book is excellent. If I had to recommend just one, it would be "Herzog." but saying that, the present book is a surprise, like a breath of fresh air. Some of his novels have a warmth and charm, and have a certain tongue in cheek approach in describing the trials and tribulations of the narrator. The humour is mixed in with the meaning of our short lives, and the future of our souls. Bellow thought that the development of realism was the major event of modern literature. That includes how we view subjects such as sex, life and death, etc. Having said that, we see two changes here. One is that in most Bellow novels the men dominate the women, or they are equal. Yes, the women often divorce our hero in other works, but here the men are like putty in the hands of the women. The story is about their attempts to get married, each to quite a different type of woman. Also, instead of one narrator, the present narrator, Kenneth, is so close to his uncle Benn that it seems like the story about two people not one. There lives are interconnected by close communication.

In case you are new to Bellow, his novels reflect his life, his writings, and his five marriages during his five active decades of writing. He hit his peak as a writer around the time of "Augie March" in 1953 and continued through to the Pulitzer novel "Humbolt's Gift" in 1973. He wrote from the early 1940s through to 2000. His novels are written in a narrative form, and the main character is a Jewish male - usually a writer but not always - and he is living in either in New York or Chicago. Bellow wrote approximately 13 novels and a number of other works.

Bellow's style progressed over the five decades. The early novels "Dangling Man" and "The Victim" were written in the 1940s, 20 years before his peak. Some compare his style in "Dangling Man" with Dostoevsky's "Notes from the Underground." Having read both I would say that "Notes" is brilliant while "Dangling Man" is at best average and sometimes a bit slow, but the prose is excellent. Changes could be seen in his second book "The Victim" in 1947. The first half is slow, but then the pace intensifies in the second half. This increase in tempo and lightness carries on in his next book "The Adventures of Augie March" - his breakthrough book in 1953 that won a National Book Prize. He changes his style in "Henderson the Rain LKing" in 1959, and then returns to the New York-Chicago theme after "Henderson." Bellow hits a new high with "Herzog" in 1964, and that book sets the tone for a number of novels that follow. The present books follows later and came out in 1987.

In interviews, and from reading the early works, Bellow said that it was difficult to make the transition to becoming "uninhibited" in his writings. That transition ended in 1953 with "Augie March" and it was refined with "Herzog." After that, there is a certain sameness to the novels. We see a bit of a break in the present novel. I will not give away the plot, but it is about two professors in the mid-west, uncle and nephew, probably in Indianapolis, not Chicago this time. There is a bit of laziness evident: he seems to use a number of quotations. But the plot is interesting, and he seems to take delight in exploring and reversing the role of man versus women. They women either ignore or try to manipulate the men, and at least one woman, Matilda, far out-classes our heroes (or as in Bellow novels, anti-heroes).

This is an interesting and unusual novel, and for myself, yes, Bellow is perhaps less brilliant, but this is still good stuff.

Not his best, but still remarkable

Not his best, but still remarkable

This isn't the one to choose if you've never read Bellow. Seize the Day (think brevity) is the place to start. From there, Henderson the Rain King, Humboldt's Gift, or Herzog make the best long reads. Augie March is the most renowned, but a good 200 pages too long if you ask me. After that, Mr. Sammler's Planet rounds out the best of Bellow. Dangling Man and The Victim are quite different from the rest, and are most interesting (I think) as points of reference to watch the evolution of a great mind.

More Die of Heartbreak ranks with The Dean's December and Ravelston as books to read only if you've already fallen for Bellow. Or, I suppose, if you're interested in reading what a Nobel Laureate thinks about sex.(For there is no book in which he tackles the topic more directly than this).There are times when the author seems to lose even himself in the mad confusion that spills from Ken Trachtenberg's head. This, I believe, would be enough to drive impatient readers away from Bellow.

But More Die of Heartbreak, like all of Bellow's work, lifts the reader above the mundane. Its force doesn't come from plot, but observation. His gift is to take the ordinary, the accepted, and acceptable and expose it for something extraordianry, corrupt, or even contemptible. His success, I think, comes from a steadfast and good-natured optimism in the face of Western decline.

... Read more

|